2025 has been a year of extremes for U.S. row-crop farmers, including grain sorghum producers. Many will harvest one of their best crops in recent memory – often referred to as milo – while they simultaneously endure some of the worst export markets agriculture has seen in the last four decades.

“There’s a lot of commodities that are hurting, I won’t deny that. But the loss of the Chinese market and any significant trade opportunities is more severe for sorghum than any other commodity,” contends Amy France, chair of the National Sorghum Producers (NSP).

That’s not rhetoric but reality for sorghum growers.

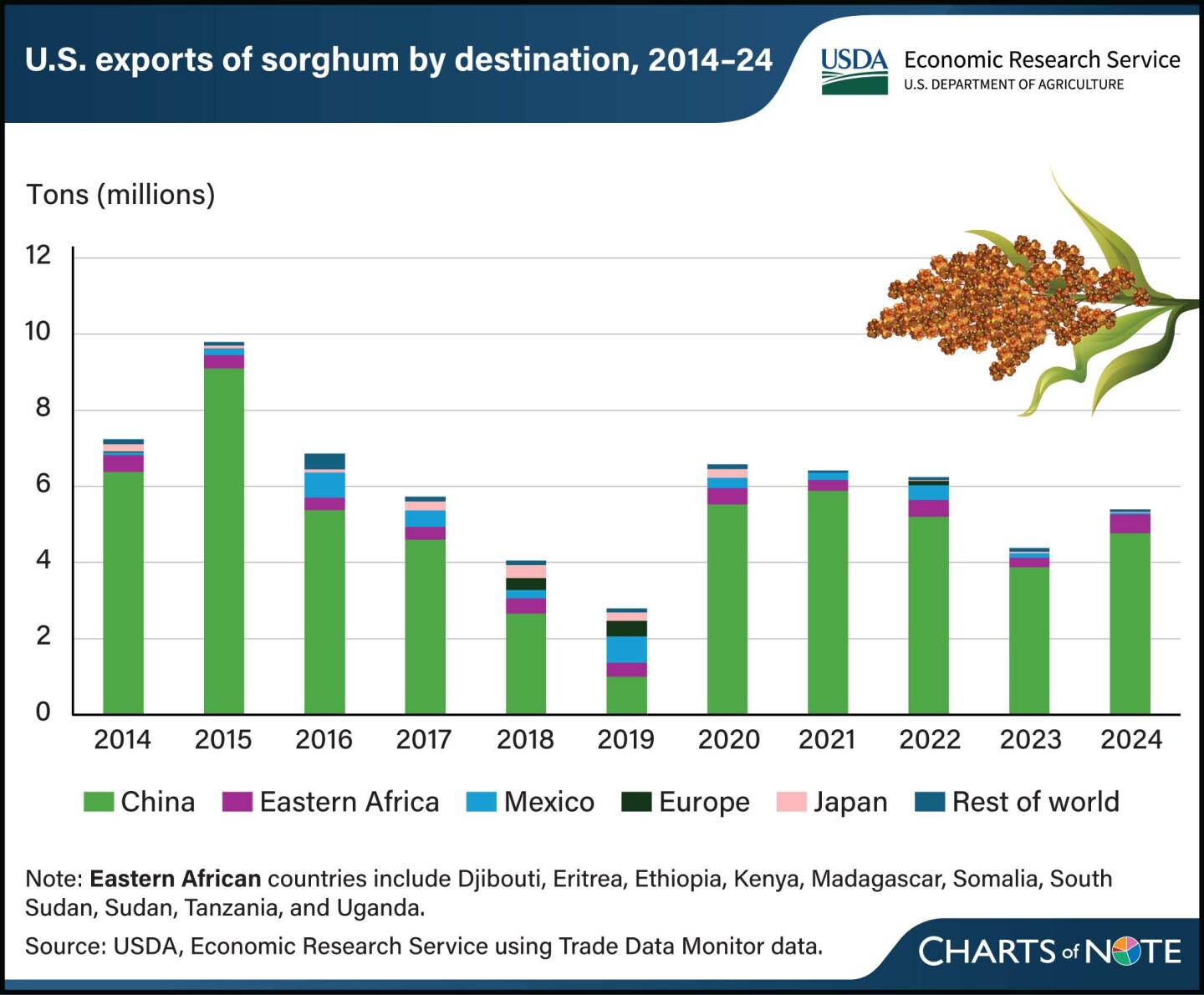

China historically purchased up to 90% of all U.S. sorghum exports. Those sales ceased in April, on the heels of tariffs and retaliatory tariffs. The remaining 10% of U.S. exported sorghum went to Africa to combat hunger. That market closed in January, when the Trump administration abruptly canceled the Food For Peace program.

Prices for the nutrient-rich grain dropped precipitously. Bids have been as low as $2.35 in key sorghum states, according to John Duff, founder of Serō Ag Strategies and a consultant to NSP.

Laser Focused On Opportunity

France is on a mission to move sorghum’s story from one of recent struggle to success. She’s working to identify new opportunities, expand upon those that exist domestically – such as with ethanol and gluten-free foods – and spur legislators to restore trade with China and other countries.

“We want trade first and foremost, but if we’re going to keep going with [these tariffs], then our farmers are going to need some help,” says France, who started her second term as NSP chair on Oct. 1.

The following week, in the midst of the federal government shutdown, France saw an opportunity for connection with legislators when others might have expected only closed doors. She flew to Washington, while NSP staff made calls to set up meetings with senators and representatives from the sorghum belt, which runs from South Dakota to South Texas, and includes Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Colorado.

“I want to ensure our producers and the next generation can continue to farm, and that equates to what we are doing on the Hill,” she explains.

A Fresh Perspective

France took a unique path to the leadership role for the NSP. The daughter of two music educators, she embraced agriculture when she met her husband, Clint, 25-plus years ago. They farm, along with their five children, near Scott City, Kan., growing corn, sorghum, wheat and black Angus cattle.

Through their local Farm Bureau, France recognized her passion for creating opportunity via agriculture policy.

“I always say Farm Bureau opened the door for me. I just got involved on the county level and then kept going. I’m not afraid to ask tough questions and dig deeper,” she says.

Some of France’s tenacity was inspired by her late father-in-law, Leon, who told her grain sorghum kept him from losing the family farm in the 1980s.

“He told me, when I went onto the board, it was the only crop he could afford to put in the ground, because it didn’t have as much input costs as other commodities, and he would reap a good harvest,” she recalls.

France keeps their conversation in mind as she works to build a better future for sorghum and the farmers who grow it.

“In navigating the current farm economy, I think about what crop can farmers afford to put in the ground and still reap a harvest? I believe sorghum is that for a lot of farmers,” she says.

“We have the best product – far and above better than what any other country can grow,” she adds. “We just need markets, and that’s what is top of mind for me.”

Your next read: New Seed Treatment Offers A Solution to Soybean Cyst Nematode