As 2026 ushers in a fresh start, agricultural economists say the U.S. farm economy has stopped sliding, but it’s far from fully healed.

The December Ag Economists’ Monthly Monitor shows month-to-month sentiment is improving, but deep structural strain remains — especially in row crops. Meanwhile, livestock markets continue to provide strength. Crop producers face another year of tight margins driven by high input costs, weak prices and unresolved trade and policy uncertainty.

“There’s cautious optimism,” the economists say, “but very little belief that 2026 will bring a meaningful rebound without cost relief or stronger demand.”

Those themes mirror the perspective of Seth Meyer, former USDA chief economist and now director of the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute (FAPRI) at the University of Missouri. In a recent interview, Meyer connected the dots between narrow margins, policy responses and what might actually move the dial for U.S. agriculture heading into 2026.

Stabilizing, Not Recovering

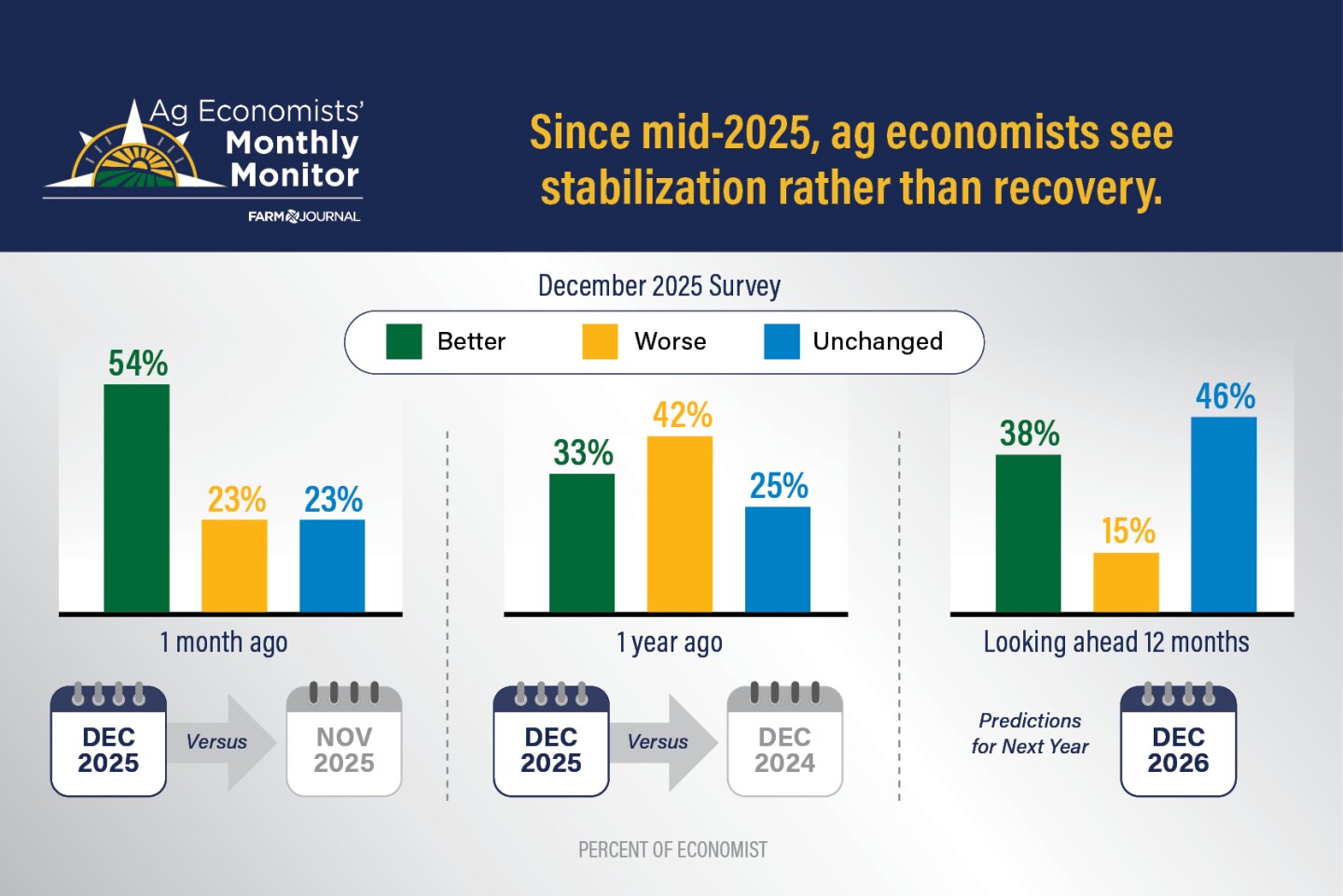

Economists see the ag economy holding its ground — but not gaining strength.

- 54% say the ag economy is somewhat better than one month ago.

- Compared with a year ago:

- 42% say conditions are worse

- 33% say they are better

- Looking ahead 12 months:

- 46% expect conditions unchanged

- 38% expect improvement

- 15% expect conditions to worsen

“Momentum has improved since mid-2025,” Meyer notes, “but tight margins have been with us for a long time. Turning that around requires demand growth, not just price stabilization.

Grant Gardner, assistant Extension professor at the University of Kentucky, tells AgriTalk’s Chip Flory: “I think as we move into kind of this next marketing year, you’re looking at what looks like a breakeven and not a loss, but breakeven still doesn’t look great after three years of breakeven or losses.”

He says even with the $11 billion in Farmer Bridge Program payments, it won’t drastically change the outlook for the farm economy.

“Purdue had a good survey about a month ago, where they looked at what were these payments going to go to, and research would show that a lot of these payments go into long-term assets, and so land tractors, but I think over 60% of producers right now are in such a tight cash crunch that you’re going to see a lot of these payments go into that short-term debt,” Gardner says.

Consolidation a Growing Threat

Economists are nearly unanimous that the crop sector remains under extreme financial stress. 83 percent say row crops are currently in a recession. That isn’t about production declines — acres and yields haven’t collapsed — but about persistently weak profitability.

“Negative returns for at least the third consecutive year across nearly all row crops,” one economist wrote in the survey.

Another said: “Margins remain below full costs of production for many producers.”

Meyer traces that back to how abruptly agriculture moved from the high prices of 2021 and 2022 into today’s tighter margins.

“We moved very quickly from a very high price environment and good profitability in 2022 to very tight margins,” he says. “That usually happens coming off price peaks, but this time it happened really rapidly.”

A minority of survey respondents argued farms are “treading water,” supported by strong land values and government aid rather than eroding further, which Meyer acknowledged aligns with how risk and safety nets have interacted this year.

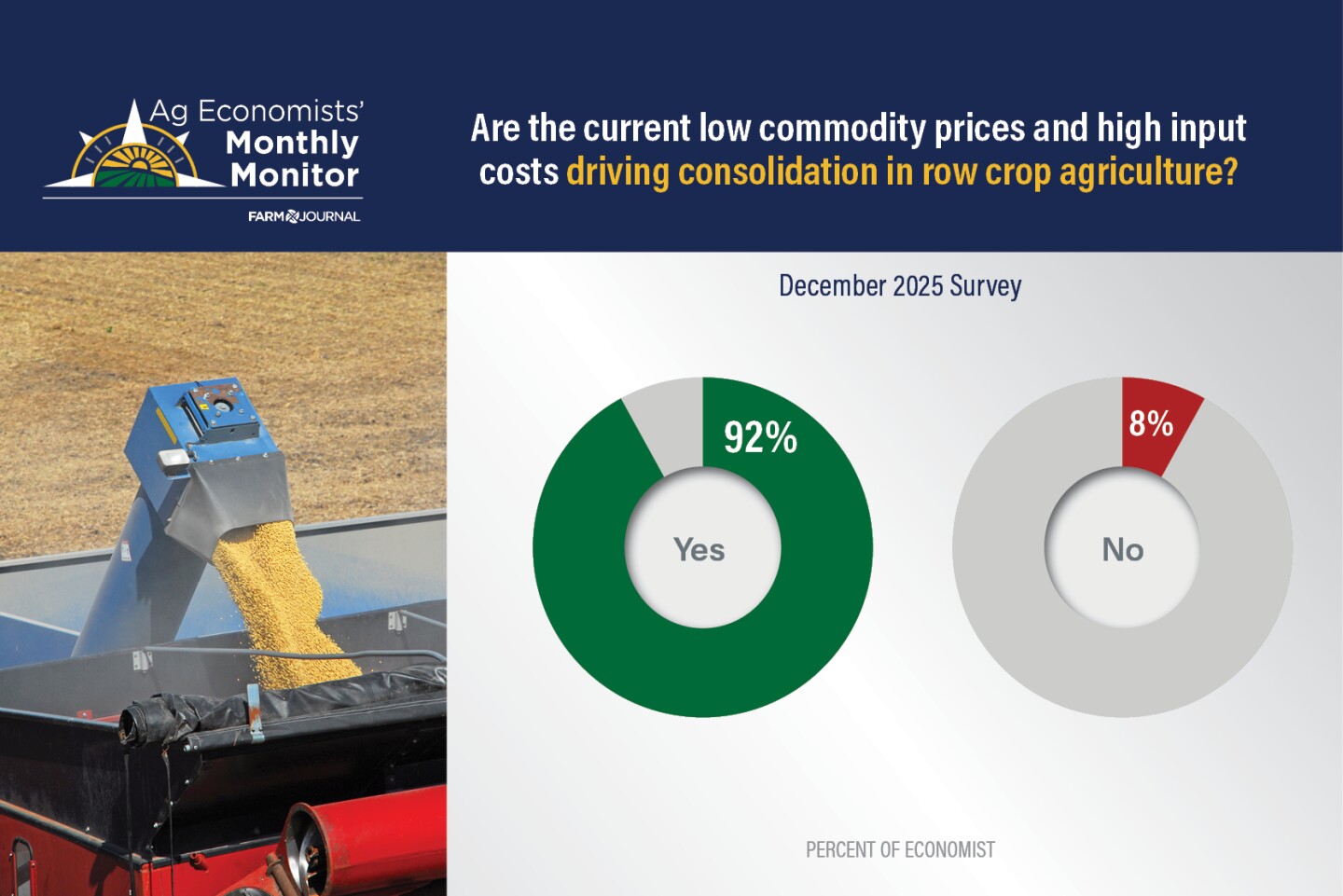

But when you look at how the current stress in the farm economy could impact consolidation, the ag economists say it’s the economic pressure combined with demographic trends causing the acceleration. In fact, 92% of them say consolidation is underway and unavoidable.

“Markets go to the lowest-cost producers,” one economist wrote. “That sorting is consolidation on the production side.”

Aging producers exiting and rent-heavy operations under pressure only add fuel to that trend, with one economist saying: “Consolidation happens because producers have to exit, not because they want to.

What’s Driving the Farm Economy Right Now

When economists were asked to identify the two most important factors shaping agriculture’s economic health today, their responses clustered around a familiar, but increasingly sharp, divide: strong demand in livestock and the protein sector versus persistent oversupply and cost pressure in crops, all layered with trade and policy uncertainty.

Several economists pointed to continued strength in beef demand, both domestically and through export channels, as a key stabilizing force. While the dairy sector is an area that shows signs of weakness for 2026.

“Livestock revenues are a bright spot,” one respondent noted, underscoring why the livestock sector continues to outperform crops financially.

Looking to 2026, economists overwhelmingly point to input costs, not interest rates, as the biggest barrier to profitability. Nearly 70% cited input prices as the largest challenge as well, far ahead of trade concerns or capital availability.

“We have too much supply and not enough demand for row crops,” one economist wrote.

Another said: “Input costs are still too high.”

Trade remains a central wild card, especially relationships with China and uncertainty around global supply. Several respondents cited trade disputes and agreements as critical factors, along with questions about the size of South American crops and how that could shape global competition in the months ahead.

Policy uncertainty was also featured prominently, with economists pointing to domestic biofuels policy, government payments and broader market signals as factors influencing both short-term cash flow and longer-term demand growth.

Overall, economists say the ag economy is being pulled in opposite directions: strong livestock demand providing support, while crops struggle under high costs, oversupply and unresolved trade and policy questions — a dynamic that helps explain why the broader farm economy feels stable, but far from healthy, as 2026 approaches.

Livestock: A Continued Bright Spot

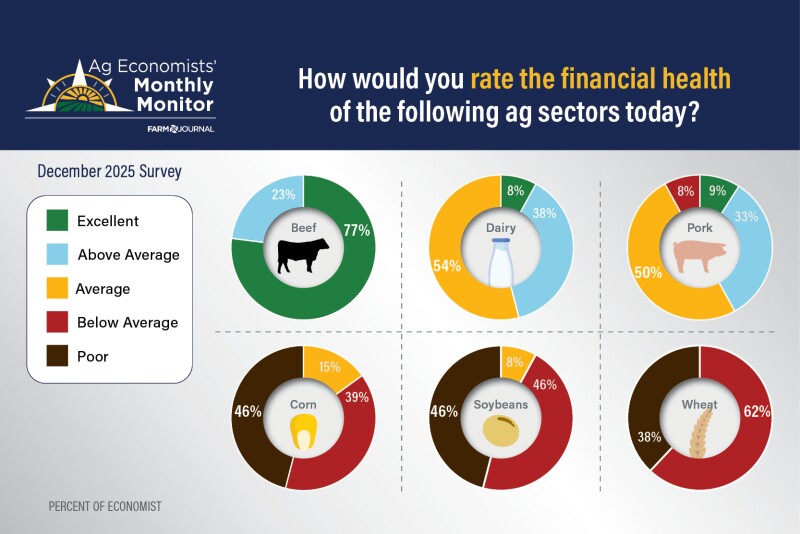

Livestock continues to stand out as the most financially healthy segment of the ag economy. Every economist surveyed rated beef as above average or excellent, supported by strong domestic demand and tight supplies. Dairy and pork were viewed as stable to moderately strong.

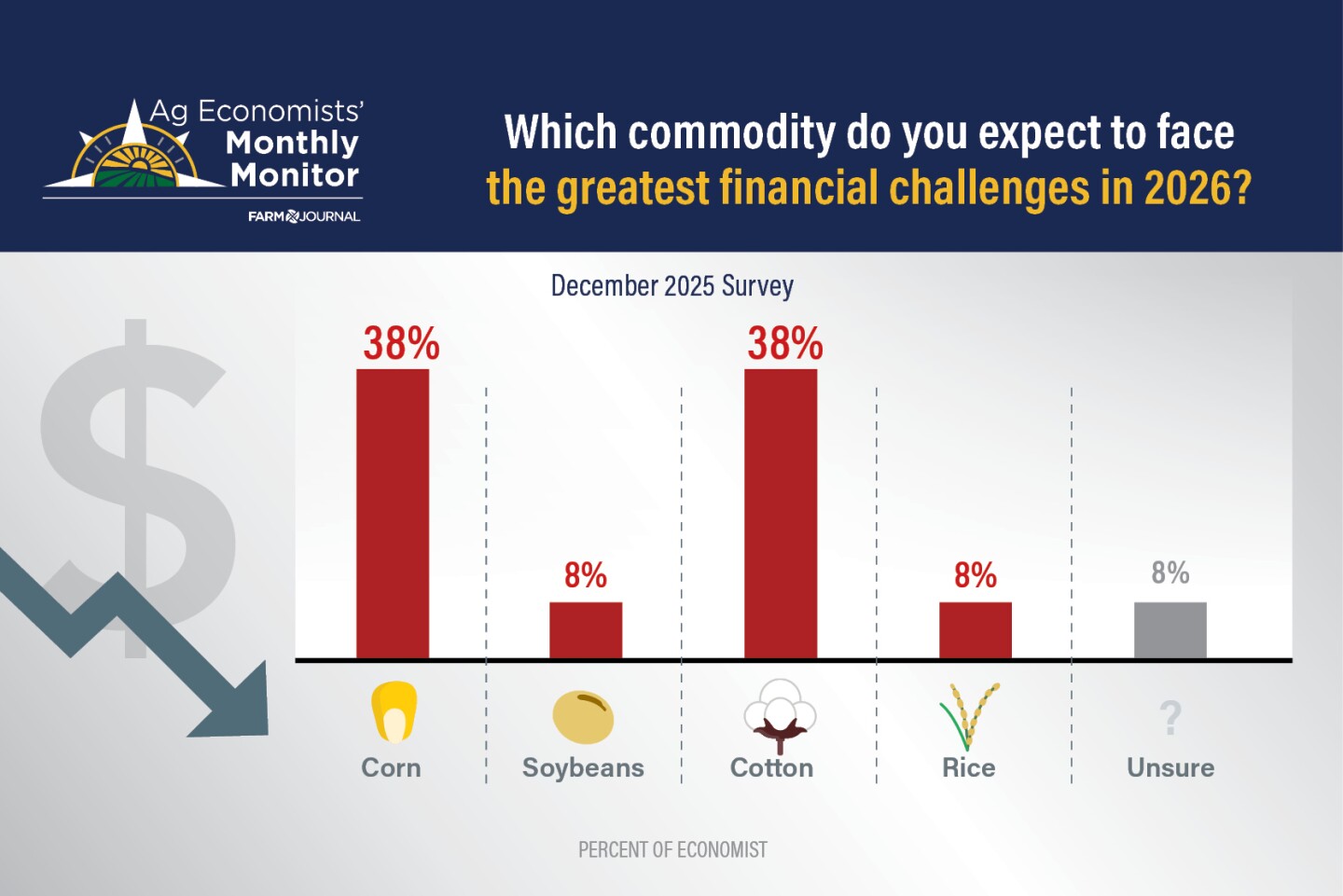

That success creates a stark contrast with row crops, where corn and cotton were cited by 38% each as the commodities most at risk financially in 2026.

What Could Move Crop Prices in the Next Six Months

Looking ahead to the first half of 2026, economists say crop prices will hinge less on domestic fundamentals and more on global supply, trade flows and policy clarity.

Across responses, South America emerged as the dominant influence, with economists repeatedly citing Brazilian weather, the size of the South American harvest and how those supplies compete with U.S. exports. Several noted that clarity around South American production will be critical in setting price direction for corn, soybeans and wheat.

Trade, particularly with China, remains another key swing factor. Economists emphasized not just the announcement of trade agreements, but whether purchases translate into actual shipments.

“China purchases of U.S. crops, but also if and when actual shipments occur,” one respondent noted, adding that details within any trade deal, including purchase commitments, will matter just as much as headlines.

Domestic factors still play a role, but economists see them as secondary in the near term. Input prices, early U.S. planting conditions and assumptions about 2026 acreage were all cited as important — especially as markets begin to trade expectations for next year’s crop mix.

Policy uncertainty also hangs over the outlook. Economists pointed to ongoing questions around trade policy, biofuels policy and broader economic conditions as variables that could amplify or mute price moves.

Economists say crop prices over the next six months are likely to be driven by how global supply unfolds, whether export demand materializes and how quickly policy uncertainty is resolved, rather than by any single domestic production shock.

Biofuels Policy: A Potential Turning Point?

One of the clearest themes Meyer highlights as a possible game changer for demand, and ultimately prices, is biofuels policy.

For economists, policy levers like year-round E15, Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) volumes, 45Z investment tax credits and how small refinery exemptions are handled could meaningfully influence demand for corn and soybeans in 2026 and beyond.

“It’s one of the places where policymakers actually have levers to help with tight margins in the row crop sector,” Meyer says.

He emphasizes that final rules on RFS volumes and how biobased credits are implemented could impact feedstock demand.

“For the next couple of crop seasons, RVO (Renewable Volume Obligations) and how EPA reallocates small refinery exemptions are big factors,” Meyer says. “Should we raise the RVO to soak up that pool like a sponge? Should imported feedstocks get full 45Z credit? Those decisions could move demand.”

On year-round E15, a long-sought policy priority for corn growers, Meyer is cautiously optimistic.

“I do think it matters,” he says. “Maybe it’s not a huge swing this year, but offering certainty and building demand over multiple seasons is supportive. Other countries like Brazil are ramping up their biofuels production too, so this isn’t happening in a vacuum.”

Policy Uncertainty Still Looms

Economists also flagged top priorities for 2026 policy action:

- Year-round E15 (row crops)

- Trade policy clarity (row crops & livestock)

- Labor reform and regulatory issues (livestock)

They also highlighted under-covered risks, which include pressure on land rents and values, labor shortages, biofuels policy details (such as 45Z credits) and slower population growth affecting long-term demand.

What Could Move Livestock and Dairy Prices in the Next Six Months

When economists look ahead to livestock and dairy markets in early 2026, they see a mix of strong demand signals, supply-side risks and policy uncertainty shaping price direction.

Consumer demand remains the cornerstone of the outlook, particularly for beef. Several economists pointed to continued buying interest from U.S. consumers as the primary support for cattle prices, even as affordability pressures rise. At the same time, some warned that a more “K-shaped” economy could begin to shift demand, pulling some consumers away from beef and toward pork.

Supply dynamics and herd trends are another major focus. Economists cited herd size, potential herd expansion and the availability of feeder cattle as critical variables. The expected resumption of feeder cattle imports from Mexico was highlighted as a key factor that could influence cattle supplies and pricing, depending on timing and volume.

Animal health risks also remain on the radar. Issues such as avian influenza, screwworm and other disease threats were mentioned as potential disruptors that could quickly alter supply conditions in both livestock and dairy markets.

Policy and trade uncertainty continues to hover over the sector. Economists pointed to ongoing questions around tariffs, restrictions on live animal trade with Mexico and the next steps under the USMCA as factors that could impact both imports and exports. Political uncertainty more broadly was also cited as a potential source of market volatility.

For dairy, economists noted that beef-on-dairy dynamics are likely to continue weighing on milk prices by increasing beef supplies while complicating dairy herd decisions.

Taken together, economists say livestock and dairy prices over the next six months will be driven by a delicate balance between strong consumer demand, evolving supply conditions and unresolved trade and policy questions, with any shift in one of those areas capable of moving markets quickly.

Acreage Expectations: Stress, Not Shock

Despite margin pressure, economists do not expect dramatic acreage pullbacks in 2026. Most expect:

- Corn: 93 to 95 million acres

- Soybeans: 84 to 86 million acres

- Wheat: 44 to 45 million acres

- Cotton: 9 to 10 million acres

Corn acreage expectations have edged lower since November, as economists backed away from another year above 95 million acres. At the same time, soybean acreage expectations have firmed, with 75% now targeting 84 to 86 million acres, suggesting stronger relative economics for beans.

“Export demand has helped keep corn acres supported,” Meyer says. “The question is whether that demand holds and whether policy supports it.”

As for acreage, the major impact on prices would be a large acreage reduction, which is unlikely.

“That’s what it comes down to, too. What I’ve been thinking about is what else can you use land for? And you’ve got the pushback on urban sprawl, you’ve got pushback on other uses for ag land. But right now, the simple fact is we’ve got way too much production. Without that slowing, or a drastic increase in demand, I don’t see prices improving to very lucrative levels,” Gardner says.

Overall, The Ag Economy Is a Grind, Not a Rebound

When you look at all the results from the December Ag Economists’ Monthly Monitor, economists paint a picture of an industry that has stopped getting worse, but has not yet found a path to durable profitability.

Crops remain mired in margin compression; livestock continues to outperform but remains sensitive to policy decisions. Government aid is buying time but not addressing structural challenges, but it’s policy outcomes, especially around biofuels, trade and E15, that could be decisive in shaping 2026 outcomes.

For now, the farm economy has found a floor. The tougher question, economists say, is whether policy can help lift it, or if it will continue to grind forward without a genuine rebound.

Related News: As Screwworm Inches Closer, When Could the U.S. Reopen the Southern Border to Cattle Imports?