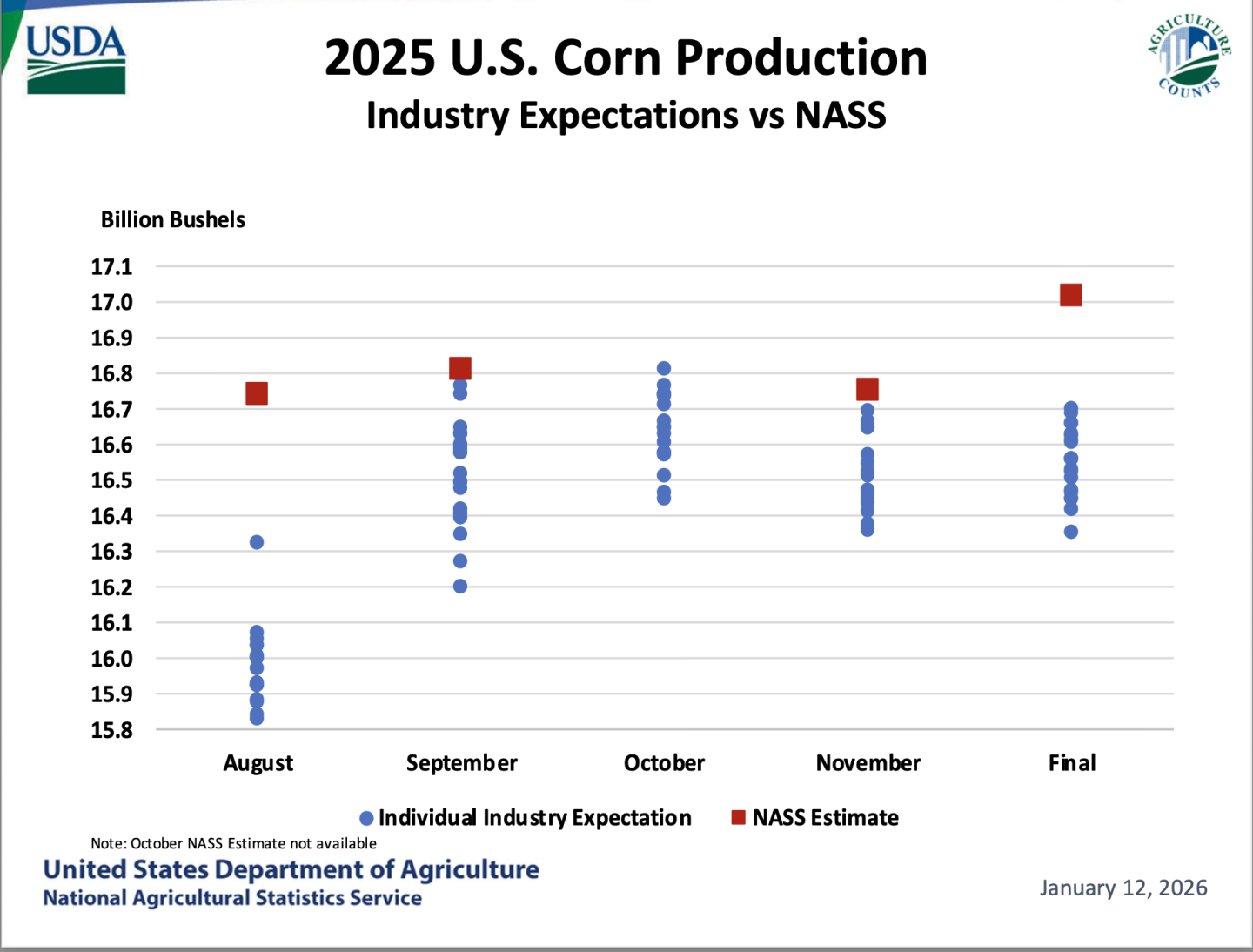

The January USDA reports, considered the most influential data releases of the year, delivered unexpected increases in corn yield, harvested acreage and total production, pushing the U.S. corn crop above 17 billion bushels and sending futures sharply lower.

Ahead of the reports, average trade estimates pointed to only minor adjustments, a typical pattern for January. Instead, USDA delivered one of the more consequential end-of-season revisions in recent years, triggering frustration among farmers who struggled with disease pressure and weather challenges during the growing season.

Key takeaways from the report:

- Corn yield: 186.5 bu./acre, well above expectations

- Soybean yield: 53 bu./acre; production at 4.26 billion bushels

- Corn production: Record 17 billion bushels

- Harvested corn acres: 91.3 million

- Dec. 1 corn stocks: Over 13 billion bushels, above trade estimates

- Soybean stocks: 3.3 billion bushels

- Wheat stocks: 1.6 billion bushels

Ending stocks estimates from USDA were also higher than anticipated with corn at 2.2 billion bushels. Soybeans came in at 350 million bushels.

The biggest surprise came as USDA raised corn yield despite expectations for a cut, driving record production and adding pressure to an already well-supplied market.

“Acres times yield,” says Joe Vaclavik of Standard Grain. “There were too many corn acres, and the yield was larger than what the trade had expected. And that combination left us with a U.S. crop estimate for 2025, north of 17 billion bushels, more than 1 billion larger than the previous record. So, the trade was caught totally off guard by the size of the crop.”

Vaclavik says not only did those changes surprise the market, but it also sparked debate.

“There’s a lot of debate,” Vaclavik says. “Was the yield number accurate? Were the acres accurate? The acres ever been accurate? A lot of debate about that, but that was the big surprise.”

Accuracy of USDA’s Latest Reports in Question

The accuracy of the reports, and how USDA came up with such a large jump in acres, is what’s aiding the farmer frustration. USDA Deputy Secretary Vaden was asked about that while speaking to farmers during the Kentucky Bowling Green this week.

“Why does USDA continue to find corn acres and similar data that destroy markets as soon as they get too high,” was the question from one farmer.

“We may not like the report, but it is not necessarily inaccurate,” Vaden responded. “USDA market moving data will be more closely scrutinized going forward, and will begin to be held accountable for large revisions if it is a fault of the agency. We plan to have NASS staff available at the Ag Outlook Forum this year to answer questions as well. We will find out in September of 2026 if their current estimates were off based on revisions made at that time. If we notice a trend in errors we will review the way the statistics are calculated.”

Small National Increase in Corn Yield, Big Regional Differences

Lance Honig, chair of the Agricultural Statistics Board and a senior official with USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), also addressed those concerns in a one-on-one interview with Farm Journal this week, offering detailed explanations on how and why the January data changed so significantly.

While the national corn yield increased in the January report, Honig stresses the adjustment itself was relatively modest.

“The yield increase we saw was pretty small, about six-tenths of a bushel from where we had previously published,” Honig says.

However, the national average masked wide regional variation. Honig acknowledges yields declined in parts of the central Corn Belt, including Iowa, where disease pressure received significant attention throughout the season.

“We did see a little bit of a drop in yield across parts of the United States, and even really parts of Iowa and such, because of some of the disease pressure,” he says. “But we also saw pretty big yield increases to the North and to the South. Obviously, all the talk and attention was on those disease problems, but even those changes weren’t maybe as large as people had expected, but the real driver, I think, was those increased yields outside of that part of the growing area.”

As Honig points out, those declines were offset by stronger results elsewhere, especially in states that are considered more of the “fringe acres” when it comes to yield production. According to Honig, the final data showed yield losses in high-profile problem areas were outweighed by better-than-expected performance in other regions.

The Bigger Driver Came in Harvested Acreage Jump

While yield caught headlines, Honig says the most significant factor behind the production increase was harvested acreage.

Planted acreage had already been revised higher earlier in the season after USDA incorporated Farm Service Agency (FSA) certified acreage data in August and September. By that point, most of the increase in planted corn acres was already known. However, harvested acreage, how many of those planted acres actually went to grain, remained uncertain until after harvest.

“When it comes to the harvested acreage, the survey is really the driver. Planted acreage absolutely is the FSA data,” Honig says. “That’s what you certify as a producer with FSA, how many acres you’ve planted. You do report your harvest intention. There’s some data we can look at there, but the reality is that’s recorded back in the spring, maybe early summer. And so until you find out what actually happened, you really don’t know for sure what that harvested area looks like.”

He says earlier in the year, USDA assumed the ratio of planted acres harvested for grain would remain consistent with what farmers reported in June, and consistent with how much of the crop went to grain versus went to silage or was abandoned, would be similar to past years.

“When we went back and surveyed 73,000 farmers after harvest and collected actual results, what we found was a much higher proportion of those larger planted acres went to grain than we had previously anticipated,” Honig says.

Final Planted Acreage Still a Surprise With Big Changes from June to January

USDA estimates farmers planted 98.8 million acres of corn, about 3.6 million more acres than expected back in March and June. Honig says that number was surprising not only based on what farmers told USDA and NASS earlier in the year, but also based on what most people watching the situation thought back in June, as well.

“This was definitely a larger change between June and January than we would typically see,” he says. “There’s really two components. You really have to break the acreage down though, because you’ve got your planted area and then, of that total, how many of the acres were harvested for grain. Obviously big changes from June to January in both cases, but from a planted perspective, we picked this almost all up back in August and September.”

Honig says planted area only increased by about 60,000 acres since USDA last published the number, but the big swing that really drove the production change in January was that harvested acreage increase.

“And so we had been inching that up as we moved the planted area up, but what we didn’t know since we didn’t have any new data about how many of those acres would be harvested for grain since June, we were assuming the same planted to harvested ratio that farmers told us back in June,” he says. “But in reality, after going back at the end of the season and getting that final data, what we discovered was that with that big uptick in acres from what they had reported back in June, a larger portion of those quote, I’ll call them extra acres, not really extra, but those additional acres, a much larger proportion of those were harvested for grain than what we would have thought back in June.”

In hindsight, Honig says, you can make sense of the changes as farmers either harvest it for grain, harvest it for silage or abandon those acres.

“And when it comes to silage, we just don’t see that much variation from year to year,” he says. “You don’t suddenly just decide you’re going to utilize a lot more silage. This is not how it works. And of course, with the weather we had this year, no big uptick in abandoned acres either. And so again, hindsight’s 20-20, but I think it does make sense that a higher portion of the large planted total this year, actually got harvested for grain.”

Acreage drivers behind the production jump:

- Planted acreage increases were mostly identified by late summer

- Harvested acreage was assumed, not measured, until after harvest

- More acres went to grain than USDA expected

- Silage use remained stable year over year

- Abandonment stayed low due to favorable weather

How the Data Was Collected

It’s also important to note how the data was collected for the January report. Honig emphasizes January estimates are built on actual, end-of-season results rather than projections.

“For the end of the season, it’s really largely driven by a large survey we do of producers, about 73,000. We do that in the month of December, which means it’s after harvest,” he says. “So we’re actually asking a large number of producers after everything’s in the bin.”

Those surveys are conducted after harvest and ask farmers directly:

- How many acres they planted

- How many acres they harvested

- How many bushels they harvested

- What their final yield was

USDA also incorporates final objective yield survey data, which comes from physical sample plots across key growing regions. So, it’s no longer forecast, and it’s actual data from the crop that’s harvested.

“We do also have final results from the objective yield survey work that we did as well, which means those sample plots that we lay out across the key growing area across the country,” Honig says. “And so a lot of data after the crop has already been not only grown but harvested that are really just giving us actual results.”

Survey Response Rate and Farmer Participation

The December producer survey had a response rate of about 40.2%, down from roughly 46% last year but still strong by industry standards.

“If you compare that to what most folks in the survey business are doing, that’s actually still quite good,” Honig says.

Still, he encourages farmers to participate whenever possible.

“My message to all farmers would be: The more response we get, the more data we have, and the more accurate we can be,” he says.

Acknowledging Farmer Frustration

Honig says he understands why producers are frustrated by large January revisions, particularly in a year when margins are tight.

“These are all data-driven decisions,” he says. “We have one purpose at NASS, and that’s to estimate everything as accurately as we can.”

He notes that earlier use of FSA data helped reduce the size of the January adjustment and says USDA will continue evaluating ways to improve the process.

“We’re going to dig in between now and June and see if there’s anything we can do to make the process even better,” Honig says.

The Part Not Many Are Saying Out Loud

Vaclavik says the changes were surprising, and whether you think they’re accurate or not, Vaclavik points out the USDA reports have produced unprecedented changes all year. He thinks there’s an underlying issue impacting the data from USDA and NASS.

“My personal opinion is that it’s not an opinion. USDA is understaffed,” says Vaclavik. “Understaffed to what degree, I don’t know. That is the simplest answer to the reason that the data has been, the word I’ve been using for acres is ‘janky.’ It’s kind of all over the place. You saw these big moves during the growing season that you wouldn’t typically see. And I know the survey response rates are never great. That was again, the case this year, but I think that the easiest and simplest and most obvious answer. Is that USDA has staffing problems. They’re doing relocations. They, I think, pay people to quit, basically. I think that’s where the problem is.”

What Comes Next

Beyond corn, Honig says winter wheat seedings came in roughly in line with last year, slightly higher than some expected, and emphasized that the March report will provide another opportunity to refine those estimates.

For now, Honig says the January numbers reflect what ultimately happened in farmers’ fields, even if the outcome surprised nearly everyone watching the market.